Accent and Knowing Your Place -Coalminers Grand-daughter Part 2

How accent can be either a mark of an interloper or of belonging

In Part 1 of Coalminer’s Grand-daughter – A Migrant in Yorkshire, we heard the story of one English family through Rachel’s story. Her family migrated from Norfolk to Yorkshire, and then from Yorkshire to America and Southern England. Comparing Rachel’s family to her own, cross-cultural writer Yang-May Ooi found that the story of migration for Rachel’s English forebears and her Chinese ones is not that different. Picking up coalminer’s grand-daughter Rachel’s own story now as an “economic migrant” (her words) down South from Yorkshire, we look at how an accent can either be the mark of an interloper or of belonging.

Still from My Fair Lady film https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0058385/

If you know me – or have heard me on my podcast or seen me on Youtube – you will know that I have what Rachel** calls a “cut-glass accent”, meaning: on the posh side of RP (Received Pronunciation).

But It was not always so.

When I first came to school in England, aged 12, I spoke grammatically correct English but with a Malaysian accent. You can hear what the Malaysian accent sounds like in my theatre show Bound Feet Blues where I portray myself as a child and also my mother, both speaking Malaysian English. Newly arrived off the boat plane, I was self-conscious about the accent, especially when English people found it difficult to understand and I had to keep repeating myself, with greater and greater inner squirming.

Fortunately, I seem to have a good ear (or perhaps no sense of self!) and over my first few months in England, I absorbed the “proper” English accent of my school friends and the other people around me. The more I sounded like the other English people, the more they included me in conversations and laughed at my jokes. I was becoming more like them. And the more comfortable and confident I felt.

The Rine in Spine

It did not occur to me back then – nor until recently – that English people might also experience a similar self-consciousness about their own accents. But, of course, there is the British class system! How did I forget that?

Why else did Eliza Doolittle go to Henry Higgins for speech lessons! She wanted to improve her lot and open a shop in the smartest part of London for the highest set in society, Mayfair. And the only way to do it was to lose her Cockney, working class accent for more genteel tones (RP) that would be softer on the ears of the upper class customers she wanted to serve, ie the My Fair Lady, (the Mayfair Lady, said with a Cockney accent).

Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle and Rex Harrison as Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady (1964) – https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eliza-Doolittle

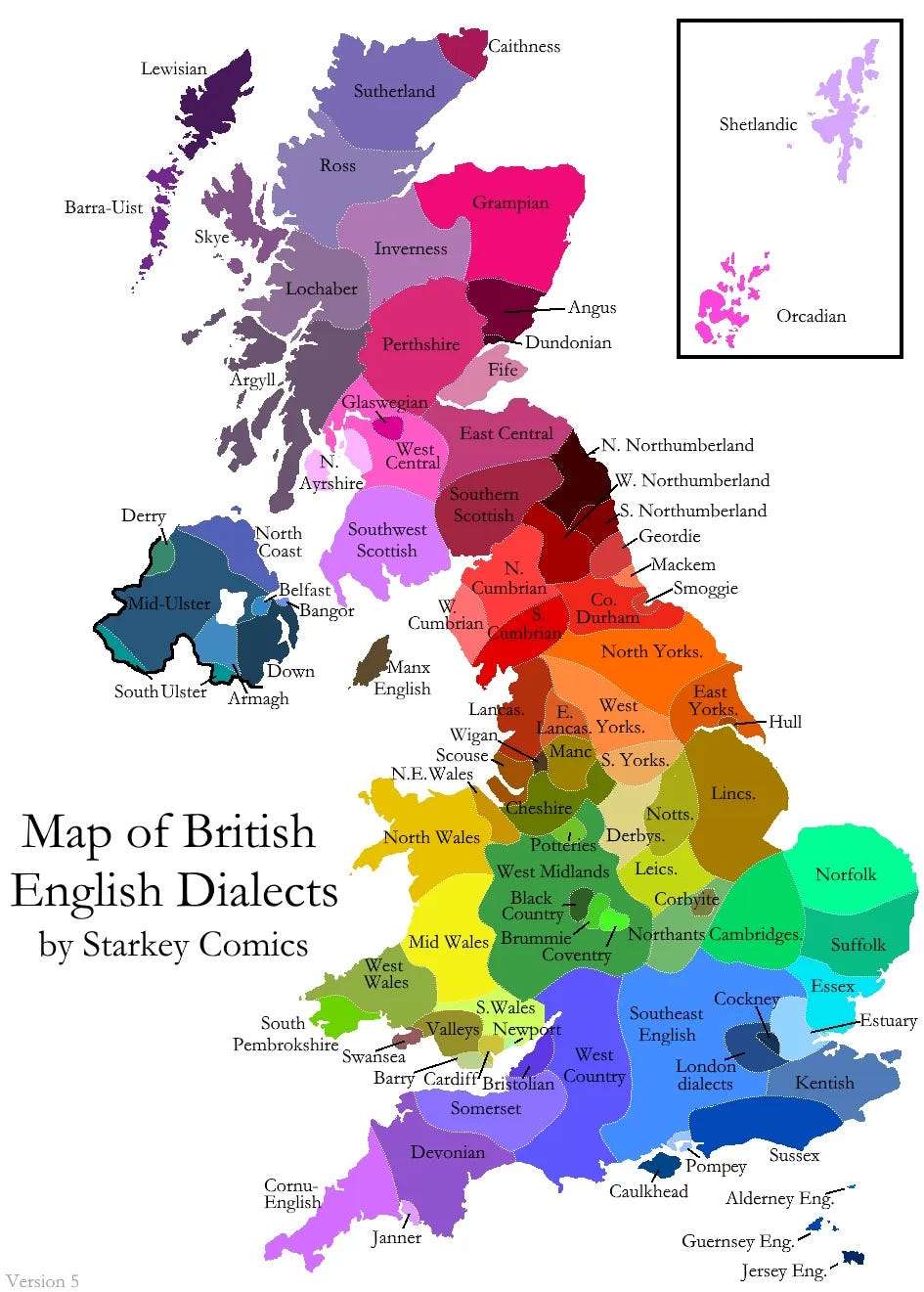

Not only that, there is the North/ South divide as well as a stereotype to go with many of the different regions in the country, not to mention Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

In the UK, accent is at the root of Belonging – or, perhaps, is the route to Belonging.

Coalminer’s Grand-daughter

We now pick up Part 2 of Rachel’s story. [You can read Part 1 here]. As we saw with Rachel’s grandfather, he was mocked – and sometimes threatened with violence – when he moved to work in the coal mines of Yorkshire because of his Norfolk accent. His son, Rachel’s father, was born in Yorkshire and lived all his life there. He was keen that he and their family speak good English but did not try to change their accents to RP – perhaps to maintain that hard-won sense of belonging to Yorkshire.

Rachel, having grown up in Yorkshire but moving down South for university and work, still speaks with a lovely Yorkshire lilt.

Down here, most people speak RP English or Estuary English. Although this has been her home for fifty years, Rachel sometimes still feels like an interloper here in the Thames Valley region because of her voice. She says, “People do sometimes speak in a mock Yorkshire accent to me and eventually I have to say I don’t like it because I don’t know whether they are poking fun at me, or maybe I’ve just lost my sense of humour! I love going back to Yorkshire and hearing people speaking like me. I’ve got a very broad South Yorkshire accent. I just enjoy it.”

Sheffield https://www.welcometosheffield.co.uk/

She describes driving back to Yorkshire. “Just when I’ve got near Sheffield, I think I’m coming home. The landscape is familiar and everything about it, even the smells are familiar, especially, at one time, going through Sheffield, there was a particular steel smelting sort of smell. It’s all those triggers that bring the comfort of childhood. And of course, as a Yorkshire person, I’m proud of it. I suppose everyone’s proud of their county but Yorkshire people are particularly proud.”

A Modern ‘Enry ‘Iggins

Someone she met once, who enjoyed playing Henry Higgins with accents, placed her intonation and a certain way she spoke as from South Yorkshire, specifically Barnsley, rather than North Yorkshire. He was probably expecting her to be surprised and pleased by his deduction. “But It upset me, actually. Because, well, I suppose I thought I’d come away from all of that and should be speaking something else. There’s still a class system in this country. So, by the way I speak, you know I haven’t been to a private school.

“And there is a prejudice against people with certain types of accent. There are Northerners who move down to London to improve themselves and there’s a thing, a cultured Northern accent. You can hear it in places like Harrogate.

“And even within one county, there are different accents – the South Yorkshire accent is different from North Yorkshire. West Yorkshire was wool. The big cities influenced how people speak – Leeds, Bradford, they were textiles and garments. Where I come from, it’s coal and steel. Every place is slightly different with their accents, and also the industry in each place.”

Neither Here nor There

When Rachel goes back to Yorkshire, despite her feeling of comfort that there is a general Yorkshire accent and most people sound like her, her voice – and ear – has been Southernised and she finds that some speak with a much broader Yorkshire accent. Also, her parents’ insistence on good English means that she does not naturally use dialect words that other Yorkshire folk might slip into but rather their standard English equivalent. So, while she is of Yorkshire, she is now also of the South.

For me, my English accent over time embedded itself into my vocal muscles and my “cut glass” voice is now who I am. It expresses the English version of me. The Malaysian version of me has not disappeared – but it is backstage, and comes dancing out when I am with my family or other Malaysians. This happens whether I am physically here in the UK or back in Malaysia. And If my English friends and my family and Malaysian friends are all in the same space with me, my two selves will skip in and out depending on who I am talking to, sometimes mid-sentence.

Me performing Bound Feet Blues where I used both RP English and Malaysian English

Like Rachel, I am of two places – Malaysia and the UK. Also, as she feels she can be located within the British class system, so I can be located too – my voice over-riding my interloper status as a first generation migrant to the UK from Malaysia.

If you would like to hear my two voices, you can take a look at the video of my stage performance of Bound Feet Blues, which is performed in RP English and also Malaysian English – go to https://bit.ly/boundfeetblues-youtube

Who am I?

Rachel has retained her Yorkshire voice, though slightly Southernised, throughout the decades she has lived here in the Thames Valley. Despite sometimes feeling sometimes mocked by others or standing out in an uncomfortable way because of her accent, she is proudly a Yorkshirewoman. I respect her for that.

Have I betrayed my Malaysian roots by becoming so English in my voice – and to a large extent, also in my manner and cultural language and behaviour? I don’t think so – because my Malaysian self is still very much present and a part of me. My English self enables me to belong here in the UK and empowers me to use language, tone, phrasing and cultural signals to create a happy life in British society. My Malaysian self emerges when there is occasion for it to – and in turn empowers me similarly to connect with other Malaysians and in Malaysian society.

I feel that if I were to use the language, manner and cultural behaviours of Malaysian English in British company, I would be very much less effective in my life here. And vice versa, using my English voice in Malaysia and amongst those who speak more comfortably in Malaysian English would make me seem arrogant and imperious to them.

This now opens up a whole new vista beyond simply language and accent all about cross-cultural non-verbal language, manners, etiquette and behaviour that can signal belonging or not belonging – which is beyond the scope of this particular story!

What Does Your Accent Say About You?

As always, I am curious about you. What accent do you have? Is it from the place where you are living now? What does it feel like to sound different from the people around you – or to sound the same as them?

What does your voice tell you – and others – about where you come from? And which bit of the British class system you might be placed in?

Map of English Dialects in the UK https://starkeycomics.com/2023/11/07/map-of-british-english-dialects/

If you – or someone you know – would like to share your story here on Curiouis Across Cultures, do get in touch. We can anonymise it as I have done with Rachel’s story – or you can be featured as you. You can contact me via the Contact page and if your story is a good fit, we can take it from there.

Or do just bring this theme up with your friends and family. I’m sure you will find a lot to talk about hearing each other’s experiences and thoughts about accents, class and location!

—

**Not her real name

–

Ref: yrks

This story first appeared on my blog about Cities and Nature, MetroWild.

–

Yang-May Ooi is an established cross-cultural writer. She is Chinese by heritage, Malaysian by birth and British by choice. Her books include internationally acclaimed novels The Flame Tree and Mindgame (Hodder & Stoughton; Monsoon Books) and family memoir Bound Feet Blues - A Life Told in Shoes (Urbane Publications). Her new Book-in-Progress explores An Idea of England from her personal perspective as a first generation migrant to the UK (due 2026). www.TigerSpirit.co.uk.

Accent feels like this secret handshake we never agreed to, says so much about class, place, even attitude. Brilliant read, Yang-May!

Very interesting… having lived in a few different countries, I’ve often wondered why accent is such a big deal but it does define who we are in front of others.